The overwhelming requirement to engage with donors

“Scandal hit charities need a strong regulator.” – The Guardian, September 2015.

“Charity fundraising techniques ‘a scandal’” – BBC, Sept 2015.

“A sweeping crackdown on charity sharks who prey on elderly and vulnerable” – Daily Mail, Sept 2015.

This piece is not about charities’ moral obligations. Nor is it an assessment of the degree to which the above headlines represented a "just desserts" following charities’ actions, or an indefensible criticism of them. But there can be no denying that, reputationally, charities have had a bruising year. Irrespective of the justification for that battering, the charity sector needs to look again at the way it drives donations if it is to rebuild its reputation, and protect its income.

That change does not have to be painful. New research suggests that a less antagonistic, less guilt-laden approach is likely to generate sustained and improved results.

So this article poses a very simple question: if you change the nature of charitable engagement, can you change the nature of charitable giving?

Alternatively, to put it another way, if charities stop hunting their donors and start farming them, can they achieve better results and fewer adverse headlines?

What is engagement?

Steven Dodds of research group Harvest describes engagement like this: “Supporter engagement is any activity that causes a supporter to invest in a charity – cognitively, emotionally, behaviourally – so that their lifetime value increases.”

In August 2015, researchers Harvest and Boy on a Beach launched a survey, via CreateConvo and ResearchNow, of 1,000 UK charity donors. Each donor supported at least one of the UK’s top 50 charities (as ranked by CBI) and had given to charity in the last 12 months via at least two methods.

Donors were asked about their levels of engagement, their attitudes and behaviours.

What and how we give

In the survey, 9% of donors made 66% of all donations to charity. 91% contributed the other 34%. By far the most typical annual donation was between £10 and £50 (48% of respondents), while the second most prevalent annual donation (at 21%) was below £10.

Only 4% of donors gave more than £250 annually.

By far the most common way of giving was through a one off donation (71%), followed by buying raffle tickets (65%) and mail order catalogues (45%).

Less than half of the sample – and bear in mind that the sample consisted of annually active charity donors – donated by direct debit.

32% of supporters said that they had been supporting their chosen charity for more than 10 years.

Generation Neutral

If this doesn’t exactly sound like a bubbling cauldron of charitable excitement, that’s because, overwhelmingly, it isn’t. When supporters were asked how close they felt to their chosen charities, neutrality was by far the most dominant emotion (79%).

The neutral stance was one that appeared largely unaffected by charity type. Children’s charity supporters were 81% neutral. Supporters of health and medical charities were 77% neutral. Armed Forces charities fared better only in a relative sense, with 67% neutrality.

The cost of neutrality

The research shows that supporters’ closeness to their charities makes a dramatic difference to the amount they give. Annual mean donation amongst neutral supporters is £60.57. Among engaged supporters the annual mean donation rises to £91.53, almost 50% greater.

What’s more, engaged supporters are 10% more likely to give a greater amount next year, compared with just 3% of neutral supporters. When they do, it will be an increase on an amount that is already 50% better than their neutral counterparts.

Creatures of habit

The contrast is stark. On the one hand, we see a picture of donation almost by habit – a frustrating charitable Groundhog Day of giving with little change. Those who have always given continue to give, and next year they will give much the same again.

The survey did not explore the effect of recent headlines and their impact on donor intentions, but it is difficult to see how donations from neutrals could do any more than stagnate, at best, in the current climate.

In contrast, those donors who are engaged are already giving more, and are more likely to give more still.

Can we convert more neutral supporters to engaged? Doing so requires the fulfilment of two key elements:

- There must be a desire among supporters to become more engaged.

- Charities need to find better ways to engage.

Some encouragement for the first of these issues comes from the survey, where 37% of all supporters said they like to have a close relationship with the charities they support, and 59% like to feel involved in the charity's work.

Yet only 13% of survey respondents make a point of reading everything their charity sends them. And 46% say they hardly ever read it or didn’t want it. If the majority of supporters really do want to get involved, you might think they have a funny way of showing it.

Redefining the relationship

Charitable engagement, the research suggests, is built on two central pillars: reach and attention. A single point of contact, a newsletter, for example, is not enough to drive engagement in more than the narrowest band of donors. Widen the touchpoints and the ways supporters can interact with you, and you create an environment better built to engage.

In the survey, and compared to their neutral counterparts, engaged supporters were 94% more likely to have had an interpersonal relationship with the charity (ie have been to an event organised by the charity, or spoken to a team member on the phone). Engaged supporters were 78% more likely to have connected digitally, by visiting the website or following the charity on social media.

Redefining the language

The language of charities that engage is different too. Traditional campaigns have focused on problems, on motivating by guilt and cultivating a culture of dependence.

Yet the research discovered that campaigns which truly engage work differently, keeping the attention by shifting control from charity to supporter and bringing the beneficiaries closer, rather than preserving the traditional "us and them" of campaign language.

What succeeds, in terms of keeping supporters’ attention, is developing an affinity with the charity’s work. Donors are engaged by progress, a sense that their donation and the work of the charity in general are making a difference. Instead of motivating by guilt, engagement means a shift to personal reward and a notion of empowering the relationship.

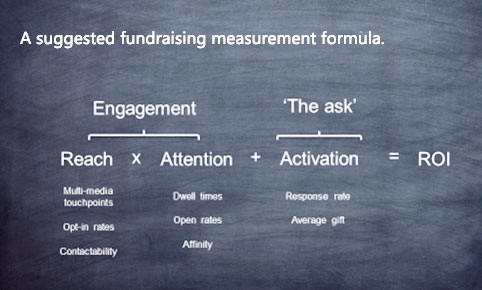

So the way forward has to be a fundraising formula which uses ongoing engagement – the cultivation of long lasting relationships – as its driver for increasing donations. The following is suggested:

The effect of engagement

How do you spot progress in making neutrals feel engaged? The language they use is telling. The research discovered that, compared to neutrals, engaged supporters were 135% more likely to feel driven and 117% more likely to feel passionate about the charity. They were 60% more likely to feel involved with their charity, and 40% prouder of it.

Are you engaging?

Is your charity a hunter or a farmer? And if you’re the former, how do you start the shift to becoming the latter? The research identified the following traits as typical of "farming" charities. These are, in effect, the identifiers of the building blocks of engagement:

- Donors are real stakeholders in my charity.

- Supporter relationships are built on openness, involvement and control.

- Donors feel proud to support us.

- We understand the emotional value we give supporters.

- We know how and when to leverage it.

- Our digital/social touchpoints are fully integrated into the supporter experience.

- Engagement KPIs are embedded across the organisation.

- Our database and IT systems fully support the increased level of integration and personalisation support which engagement requires.

Most supporters want to be involved. When they are, their own passion, drive and pride create the virtuous circle that drives increased donations.

Even without the adverse headlines of the past year, this research into the value of engagement – of farming not hunting – would seem to offer a compelling reason to change fundraising approaches. In the current climate, a strategy that places relationship-building at its heart seems all but irresistible.