Understanding charity investment performance

Reflecting on markets in 2013, most charities might be forgiven for feeling very satisfied by the performance of their investment portfolios. At first glance, results of the charity peer group investment performance indicate that it was a vintage year. The WM Charity Fund Monitor increased by 15.5% for the year to 31 December 2013, while the ARC Sterling Steady Growth Charity index rose by 14.6% over the same period.

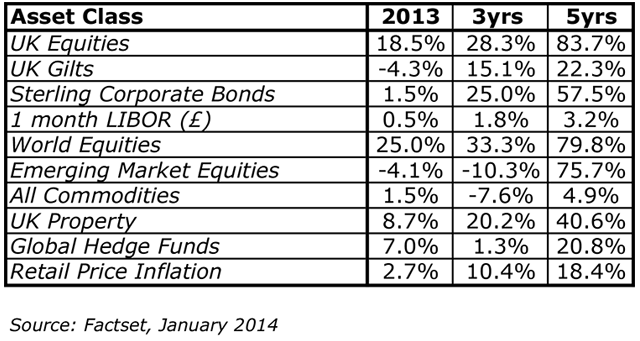

A detailed breakdown of asset classes is given in the table below for the last 1 year and cumulatively over 3 and 5 years. Charities which invested into UK or international equities did well over all time periods, reflecting long term trends, given the higher risk that comes with investing into equities. UK property did well too, as measured by the IPD index, and offered useful income given the strong rental yields in London and South East. Commodities and emerging market shares fared less well in recent years and investors were not paid for taking risks in these areas.

If this is reflective of general charity performance, trustees may not be currently too concerned about their investment portfolios. At some stage, the rhetorical debate among trustees will arise and this predominantly revolves around what is an appropriate return for a charity. Some like to take risks in order to get high returns, while those with more conservative appetites may opt for lower growth with a less stressful path. Others may be in need of regular income from their investments, at the expense of capital growth.

Whatever the overriding investment policy of a charity, the measurement of performance is vital in establishing how well it is doing in meeting its objectives.

Charity Commission guidance on investment states that charities invest so they can further their charitable aims. While each charity may be unalike, with differing aims, objectives and resources, trustees should be clear about exactly what the charity is trying to achieve by investing its funds.

Charities which are reliant on other fundraising streams for their income may need to have a different investment policy to a grant making charity which relies solely on the income derived from its investments.

Time horizons

Time horizons and longevity of investment are also an investment factor. Charities have a duty to use their money on good causes, giving due consideration to balance the interests of current and future beneficiaries. Certain charities will have a mission to spend their capital over a predefined period, while most will aim to exist in perpetuity with a need to protect their capital value from the effects of inflation.

Annual charitable expenditure will be met from capital gains and income, if investing on a "total return" basis, or from income alone if the charity is restricted by having a permanently endowed status.

Whether or not the charity invests for short or long term benefit, it is the trustees who have to uphold a duty of care over the investments. Behavioural economics would suggest that most individuals tend to think on a short term basis and are adverse to any losses in capital, therefore conscious of risk.

As most charity trustees are appointed for a limited period, typically 6 to 9 years, there is a tendency for them to take short term or lower risk decisions with investments. They are unwilling to allow a disaster while "on their watch". This is in contrast to the fact that the charity may have a long term objective which can take higher risk to achieve better overall returns.

Undeniably, performance matters. Given all the factors that lie behind charities' investment policies, trustees' behaviour will relate to the rise and fall in their investment portfolio. Whether or not they decide to delegate investment decisions and take independent investment advice, charities need to review their investments "from time to time".

Trustees and investment managers have a tendency to interpret performance in a number of ways and attention to this is usually highest when there are significant markets falls, as those who were investing in 2000 or 2008 will remember.

Performance differences

It is important to establish the difference between absolute and relative performance.

• Absolute performance is the measure of the portfolio in isolation to anything else. It is a measure of the capital and income returns, usually after the costs of investment and any taxes.

• A relative return usually refers to the absolute performance of a charity in comparison with another measure. This could be another charity, a peer group of charities such as WM or ARC, a market index such as the FTSE 100, a composite of different market indices or a particular measure typically related to inflation or cash.

An absolute performance is useful when comparing returns to charity expenditure, be it income or capital levels. This measure is vital for producing financial plans and setting appropriate reserve levels, although past performance is not a good guide for future returns!

Trustees looking at relative performance must follow the old idiom of not comparing apples with oranges. As the table of asset performance demonstrates, different assets will produce very different results.

When a charity invests in a mix of different assets they should only compare performance against a measure which is similar to this. This is why strategic, or long term, asset allocation is so important to meeting the financial objectives of a charity. If the investment manager decides to tactically or in the short term move the charity's overall asset allocation away from the long term strategy, a relative performance measure is a good indicator of investment skill.

The point at which an investor takes a profit in an investment after good performance is key. It is a question many will be pondering after a weak January for markets at the start of 2014, given the degree of jitters in the emerging market currencies and weak economic data on developed nations. Profit taking will be largely down to the investment style adopted, but many charities tend to buy and hold solid companies and secure bonds or property for long term capital growth and income.

Investment risk

Many charities have tended to focus exclusively on investment return, with little concern for investment risk. Risk is increasingly used in conjunction with investment return and is often found in investment managers' reports.

This is a subjective measure that will be based on a number of factors and can be used to measure the quality of an investment. It offers charities a measure of the amount of risk a portfolio is taking to achieve the stated return. Some measures will offer overall performance on a risk-adjusted basis and others will look at the amount of risk taken for each percentage of return.

It is important to have some understanding of the different risk measures and how this relates to a charity’s overall investment portfolio. The overall risk should match the level of risk trustees are willing to take in their investment policy. It should also be a good indicator of how efficient an investment manager is. In a perfect world, trustees should look for the best level of performance with the lowest level of risk.

Taking all these performance factors into consideration, it is not surprising trustees without investment knowledge or a good grasp of maths can get confused. Taking a limited view of performance measures can lead to misguided or jaundiced opinions by trustees and advisors about certain investment managers.

As trustees review their investment performance and those who manage them, it is vital that all measures are looked at on a comparable and objective basis. As future performance is largely based on the past, reviewing different assets and managers needs to be undertaken with great attention to detail and care. This will be the subject of my next investment report.