Latest investment

Click on the headlines of your choice.

Being clear about your investment goals

“If one does not know to which port one is sailing, no wind is favourable.”- Seneca the Younger.

All charity trustees look to investment managers to produce results which allow them to support their own charitable activities and meet future funding objectives.

However, much like the weather, investment markets can be almost impossible to predict. The best laid plans of many charity investors can quickly come unstuck in volatile and unpredictable markets, and indeed the more tumultuous conditions become, the harder it can be to stay your course.

That is why the investment goals for any charity must be carefully thought about and planned before embarking on the journey. Like a sailor preparing for a voyage, a solid plan – and a clear destination – are the most important stages of the whole expedition.

Real returns

When a charity starts investing it is vital for you to first understand exactly what it is you are looking to achieve. For most charities, protecting gains and achieving a real return should be the core objective.

This is particularly true for charity trustees because donors will naturally want to see them being careful and responsible stewards of their capital. It means most investment committees should therefore be targeting an inflation plus return (known as a real return), rather than trying to achieve outperformance of an arbitrary benchmark or peer group. The idea being to grow the real value of the charity’s capital and therefore protect the future purchasing power of those assets.

It is important for charities to realise that in investment there are no risk free gains, so it is not possible to completely avoid the possibility of making a loss.

Ongoing positive return

However, there are ways to manage this risk. Achieving an ongoing positive return, rather than the feast and famine one often sees trustees having to cope with, requires a different approach to the one adopted by many investment providers, and arguably a more disciplined one.

Ideally the focus should be on volatility and managing the scale of performance highs and lows. One of the most well documented and established ways to do this is diversification. Put simply, this means investing in a portfolio or fund that has the ability to access a range of different types of assets.

In the same way a sensible sailor still packs wet weather gear even on a sunny day, in a portfolio you need a wide range of assets doing different jobs. By having assets which react differently to each other in different market environments, it means the overall return is hopefully smoothed, with violent swings in either direction avoided.

Inflation as your compass

Rather than trying to shoot the lights out one year, only to see returns head south the next, the emphasis should be on protecting gains and achieving a real return.

All charities need to protect assets and thus avoid spending more time than necessary making up lost ground. Protecting future purchasing power should be a key objective. One of the best ways to achieve this is by benchmarking investment returns against inflation and targets that seek to beat it by varying degrees.

Protecting volatility

Encouragingly, one is seeing that attitudes among clients are shifting, with long term returns and protection from volatility increasingly becoming more of a focus. Although the individual target for every charity will vary depending on specific objectives, aiming to deliver returns above the Retail Prices Index (RPI) inflation level is a prudent destination to aim for.

By targeting inflation specifically, charities can ensure they are doing their best to keep pace with it. After all, it is no comfort to anyone to know a portfolio has fallen by as much as the benchmark in tough times. Instead, charities want their portfolios to stay on course and achieve their goals. Crucial to this success will be having the ability to adapt and diversify to market conditions, rather than being trapped in underperforming assets due to the benchmark they’re tracking or measured against.

Incredibly, many advisers do not focus on this overall goal. Instead, they follow the mantra that relative performance is more important than real returns. This attitude needs to change. At the very least charities should consider splitting their investments to use both approaches. This should mean that whatever the weather brings they are better prepared.

Multi-asset approach

Charity investors can aim to achieve an inflation linked return in a number of different ways, but one thing is pretty consistent - they need to have access to a variety of different returns. Again, portfolio diversification is key.

Investing across the vast spectrum of assets available – from fixed interest securities such as gilts and bonds to global equities, and all the way to commodities such as gold – means investors will hold a spread of assets which offer different risk and reward profiles. Combined with an active allocation approach which regularly monitors and adjusts portfolios as markets shift, this collection of asset classes can help to reduce the impact of shocks in markets which can seriously harm portfolios.

As ever, it is the investment manager’s job to make allowances for such shifts, and to manage the expectations of charities when it comes to the risks and rewards on offer. As Seneca the Younger says, no wind is favourable if you don’t know where you’re sailing to. It is an investment adviser's job to help charity trustees maintain focus on this end goal and overall investment destination.

Remaining flexible

Following years of benign inflation and soaring markets, the outlook has changed in 2017, with prices rising and many stock markets showing elevated valuations, thus posing significant challenges for 2018. So while the current and future environment presents these new challenges, if investment managers can remain flexible and keep their eye on the end goals for charities, they can still bring their ships into port safely.

The reality of the impact of investment skill

In June 2016, the Brexit referendum began a prolonged period of political instability. Traditional polling methods have become less reliable, making for more shocks in election outcomes across the globe. This has been reflected in markets.

While the FTSE 100 has climbed steadily since Britain voted to leave the EU, it has been a bumpy road to get to current levels. Similarly, the NASDAQ 100 index has been on a twisting climb throughout surprise elections, snap elections and increased uncertainty.

During these moves, there have been plenty of opportunities for an active fund manager to trade in and out, take profits, average down and up, and actively and skillfully navigate the waters. Indeed, recently, the active management versus passive management debate has focused heavily on the application of professional skill in order to beat the market return.

However, the market return is nothing more than the sum of the returns of its constituents. A market return can be outperformed in just two ways: by selecting between market constituents (stock picking) or by adjusting exposure to all or part of the market (market timing).

Media coverage of the debate between active and passive has mainly focused on stock picking as an application of the skill of a fund manager and a reason to justify management fees. It has become clear that the vast majority of asset managers are failing to add value through stock picking, especially true once their fees are added into the equation.

Portfolio management

Many investment managers have reacted to this change in investor perception by establishing portfolios using passive ETFs (exchange traded funds) as building blocks. This approach allows charity investors to benefit from the reduced cost associated with rule based ETFs, and is often presented to charities as a passive solution.

But, while this strategy means that managers aren’t focusing so much on stock picking, and are looking to gain increased cost efficiency, it continues to rely on the manager’s skill in timing markets. The manager adjusts the strategic asset allocation over time (or applies a tactical asset allocation, which has the same effect) in an attempt to maximise portfolio returns while protecting the investor in turbulent markets.

While this offering uses traditionally "passive" products in ETFs, charity investors should realise it is not a true passive proposition. Even though the manager is no longer stock picking, he or she is still trying to time the market, a skill based activity. It eliminates one element of skill associated with active management but firmly retains the other with the aim of delivering a better than market return.

This style of portfolio management is perhaps best described as a hybrid active strategy. It pays lip service to the academic conclusion that active managers do not add value, but also is comforting to investors who may feel more relaxed in the belief that they need to be actively advised across market cycles. It also very neatly allows professional managers and investment consultants to preserve and justify their fees while, at the same time, extracting cost from the underlying fund layer.

Analysing the evidence

This begs two questions for charity investors: whether trying to time the market works and whether managers can justify their associated fees.

The answer to both questions is likely to be "no". Numerous studies have concluded that there is little or no evidence that managers add value through market timing. Neither Chang and Llewellen nor Henrikssen found evidence of consistent market timing skills within the mutual fund universe. In later studies, Jiang and Becker et al confirm these findings.

If one looks closely at this issue one can find data that is even more pessimistic. Recently, a study reviewed the performance of several third party managed portfolios with a view to comparing their performance relative to that implied by their strategic asset allocation.

It measured the portfolios over a period of eight to ten years and found that performance is just not up to par, even before fees and charges have been taken out. More surprisingly, the single largest component of shortfalls has been intentional deviations from the agreed risk profile through tactical asset allocation processes and through risk reduction measures in turbulent markets; in other words, through trying to time the markets.

Even famous and "big name" managers are falling prey to a behavioural bias. They tend to be over-defensive and sell during market falls. Unfortunately, this means that they tend to miss out on rewards during market recoveries. The opportunity cost of consistently running at a lower risk than is specified in the mandate can mount up over time. The market volatility of the last year means that there have been plenty of opportunities to test this.

As markets have risen and fallen across 2016 and 2017, being able to time the markets should have provided a number of great opportunities for a hybrid-active manager to show the value of its skill-based approach.

Recent market experience

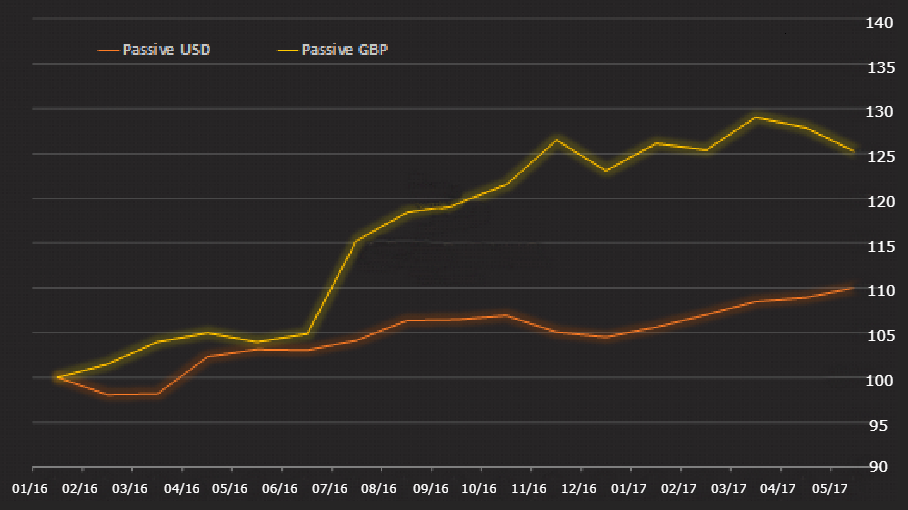

But this hasn’t happened. Across this period a low risk, passive portfolio, expressed in US dollars, produced 10% returns. In pounds sterling, that’s even higher at 25.2%. However, if we look at the performance of a hybrid active fund such as the 7IM AAP (Asset Allocated Passives) Balanced Fund. We can see a return of only 12.5% in sterling terms. Even worse, it underperformed its own benchmark by 1.2% in the process.

This suggests a simple conclusion: in the majority of cases, investors should benefit by targeting the generic market return as opposed to paying for active or hybrid management.

Passive investing skill

The supposed benefit of employing the traditional manager skills of stock picking and market timing have been shown time and again to be extremely elusive. Charity investors should be careful of working with a manager that is offering a hybrid strategy which still relies on a manager to be able to predict the future and react before events have even happened.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that there’s no skill in investing. Even passive investment needs skill and understanding, especially at the design stage. Properly constructing a passive portfolio must begin with a high level risk allocation focused on the investor as an individual. A granular set of indices representing the relevant investable universe will then form the benchmark for measurement of performance.

Following on from that, the ETFs and index funds that track the benchmark must undergo a screening process that looks at methodology, tracking error, liquidity, costs, tax efficiency, structure and counterparty risk.

When charity investors consider a passive approach, that assessment and screening process is where the adviser earns his money. Selecting the wrong products can mean disaster as the full investable universe is not addressed, or the correct benchmark is not achieved. If this first process is managed correctly, then the skills that don’t work - stock picking and market timing - are less necessary, generally resulting in better performance and a safer journey through the markets.

Passive investing for charities

What does this mean for charity trustees? The charity sector needs to become better at measuring the net benefit it achieves over the investment cycle through paying for subjective management skills. Manager performance should be regularly reviewed against the performance of the relevant market benchmark, and not against the main bunch of a collectively underperforming peer group. Consistent underperformance should be eradicated.

Most charity investors have at some point defined a strategic benchmark, but relatively few rigidly track the performance of their portfolio and its constituent parts against that marker. Benchmarks tend to be treated as theoretical concepts. In fact, they represent the highly achievable objective market return, and should be front and centre for anyone with fiduciary responsibilities.

As a start point, one would advocate that trustees should set up a relatively small passive portfolio designed to replicate the charity’s stated market benchmark. This will provide ongoing tangible evidence of the intrinsic market return, net of all fees, against which the charity's active portfolios and its investment consultants can be measured and held to account.

"It is important for charities to realise that in investment there are no risk free gains, so it is not possible to completely avoid the possibility of making a loss."

How trustees should be achieving investment oversight

At a time when the world is changing at an unprecedented pace, the role of the charity trustee is becoming increasingly complex, including the delivery of reliable, long term investment returns and stable income.

Macro-economic and political events dominate the news headlines, fuelling uncertainty exacerbated by short termism. Charities must look past this noise by focusing on well structured, well governed investment portfolios which deliver enduring investment solutions. Here are the factors that trustees should consider to achieve this objective:

Investment committee

Charity trustees have overall responsibility for the investment of their funds. They can delegate the management of their investments to those with relevant professional experience, whether internal or external, and pass oversight of portfolios to a finance or investment committee. This committee must report to and advise the trustee board, but trustees should be aware that they are ultimately responsible for any decisions made.

The committee could be formed of the whole board of trustees. However, in the interests of efficiency and to ensure that relevant knowledge and experience is brought to bear, many charities decide to form a separate investment sub-committee to advise the trustees and to oversee an agreed investment policy.

The added advantage of this approach is that other appropriate internal appointments can be made, such as staff dealing with finance and budgets, on a more frequent basis. In addition, external advisers can be included to offer specific investment or legal experience, which may come from involvement with other charities, bringing an informed yet independent perspective.

Investment policy

A written investment policy provides the framework for making informed decisions. It helps trustees manage their resources effectively and at the same time demonstrates good governance. Regardless of size, charities with investments must have a policy, which must be agreed and signed off by the trustees and reviewed periodically.

The policy must take into account how trustees intend to manage the assets. The size of funds available for investment may steer a charity in a particular direction. For example, investment managers generally have a minimum value that they will manage in a segregated fund. For large sums, charities may wish to appoint more than one investment manager, covering different areas of specialisation.

The policy must also reflect an appropriate investment horizon for return generation. Clearly endowments have a long term horizon. These funds lend themselves to investment in "real assets" (e.g. equities and property) which offer the potential for capital growth or inflation. However, other funds exist to provide liquidity or funding for a known purpose. These assets should not be put at risk and need to be readily available, and such funds should be invested in "financial assets" (e.g. bonds)..

A good investment policy should also balance a charity’s requirements, such as capital preservation and income, with risk tolerance. An investment policy needs to serve two masters – providing income for the present, and providing for the future by ensuring assets at least maintain their value in real terms. Trustees who fail in this last regard are likely to see the income from their investments fall.

A strong investment policy will define a charity’s strategic asset allocation and provide the flexibility for tweaks on a more granular, tactical level in response to short and medium term market trends.

Asset allocation

Charities’ investment portfolios should be suitably diversified across asset classes to match their liabilities. Diversification is useful for reducing specific risk such as too large an exposure to a single sector or stock. It can be viewed from several angles, such as the number of asset classes selected or the holdings within each class. In addition to core instruments like bonds and equities, other classes such as alternatives can be included. Each of these can be further subdivided down into different geographies, currencies and strategies.

This does not mean that charities must hold a diverse range of assets if one asset class, such as equities, is appropriate. Few individual managers have proven experience in every asset class and investing with more managers could significantly increase costs. Diversification should be properly scrutinised – more holdings do not always deliver greater diversification, but can prove complicated, opaque and expensive.

Charities must also decide how they want to split their investments across financial and real assets. Financial assets, such as bonds, can provide security of capital and income, but offer no protection against inflation or rising interest rates. Real assets, such as equities and property, can provide capital growth and income growth, but are considered to be higher risk.

Asset allocation and diversification must be carefully assessed on an ongoing basis. Past investment cycles have shown us that the values of bonds and equities normally move in the opposite direction, providing useful diversification. This was particular true before 2008, the depth of the financial crisis. However, from 2008 to 2014, while smaller moves were in opposite directions, the general trend for both asset classes was upwards. From 2014, both the trend and shorter term fluctuations have been synchronised upwards.

As one asset class has not provided a foil for the other recently, the mix of assets between bonds and equities has been less effective in reducing the overall volatility of an investment portfolio. The implications are particularly interesting when considered in conjunction with income generating potential.

For long periods, UK government bonds (gilts) have yielded more than equities and so were the core income generating part of a portfolio. However, since the financial crisis, equities have yielded more than gilts. We are now in a relatively unusual situation where equities not only provide prospects for capital preservation, but also offer a higher current income.

Manager selection

Once charity trustees have determined strategic asset allocation, they will often pick professional investment managers to manage all, or sections of, the portfolio. Good manager selection is key as many fail to outperform the market. It is therefore essential to examine the organisation that a manager works for: Does it have a good reputation? Is there a house investment style? Will you have direct contact with the portfolio manager(s) or solely with relationship managers?

Trustees should also research and get to know individual portfolio managers and the way they work. Do they have integrity, skill and experience? What is their long term performance like? What is generating their performance? How is performance relative to a benchmark and/or peers?

Trustees must also consider a manager’s investment process and approach to managing risk. Does it make sense? How are stocks selected? How is the portfolio constructed? How is risk measured and controlled?

Oversight standards

It is vital for trustees to ensure that monitoring and reporting are up to scratch. Managers’ performance should be assessed against appropriate benchmarks. This may be as simple as a single index such as the FTSE All Share Index for a 100% UK equity portfolio, or a mixture of recognised indices in a proportion that reflects the strategic asset allocation. Charities with a 70% equity/30% gilt portfolio might have a blend of 70% FTSE All Share and 30% FTSE Actuaries UK Conventional Gilts All Stocks, for example.

There are two ways in which an active manager can add value. One is via stock selection and the other by tactical asset allocation around a charity’s strategic benchmark. However, charity trustees may wish to exercise some control over how far a manager has discretion to move from the strategic asset allocation. This can be done via benchmark bands, which might limit discretion to move 10% either side of the benchmark without consulting the investment committee.

In terms of reporting, trustees must also decide how much information they want from managers and how often. An appropriate solution may be a quarterly valuation and report which summarises transactions, income and other portfolio data for that period. This can be accompanied by a written report detailing what has occurred during the period, what action the fund manager has taken and why, and an outlook for the months ahead.

Personal meetings

It is also important that trustees meet fund managers in person on a regular basis to ask questions and obtain any necessary clarifications. Trustees and managers must have a consistent reporting process in place and review holdings versus the charity’s investment policy. Most importantly, the charity’s trustees and investment committee must demonstrate an ability to adapt to changing circumstances and take recommendations which can improve stakeholder outcomes to the trustee board.

Charities being able to invest in commercial property

In an environment of continued high levels of political and economic uncertainty, it can be difficult for charities to find attractive income streams and value growth from their investments. Charities support a very diversified range of causes, which place a broad range of funding needs on charities endowments and incomes. However, one thing they do all have in common is seeking superior returns from their investments whilst not betting the farm.

It is certainly a challenge for charity finance managers and bursars to maximise the potential returns from the funds they manage. We have been in a low interest rate environment for more than 10 years and charities cannot leave material deposits in bank accounts where the rates of return will be extremely low. In order to achieve more attractive returns they have had to consider a range of asset classes.

Bond yields are low and the volatility of equity prices is not always compatible with a charity investors’ objectives and appetite for risk. However, for a medium to longer term charity investor commercial property offers attractive income and capital returns.

A common misconception is that investing in the commercial real estate market is only possible for charity investors with substantial endowments. However, a diversified property fund, which invests in the three principal real estate sectors - industrial, retail and offices - is an ideal way to gain access to the property market without the large capital and time investment required to build and manage a portfolio from scratch.

Resilient return

Figures released by MSCI demonstrate that commercial real estate offers a resilient return for investors. Looking back over the last 20 years, average income returns of a little over 6% and average capital returns of a little over 3% can be delivered and yet charity investors are finding it particularly hard to locate commercial property investments offering attractive income returns.

However, the rental income from a diverse commercial property portfolio is dependent on a very broad occupier base, from a wide range of industries paying their rents. This reassures investors of the resilient nature of the distribution to investors. Property capital values can cyclically increase and decrease but the income received is resilient and strong.

For those charity investors who are working off a total return distribution policy and who are investing over the medium to longer term, the returns from a diversified commercial real estate fund are supportive of them achieving their targets.

Investing directly in commercial real estate can be demanding on the investor’s time and requires specialist real estate knowledge. Many charities which would like to access the returns delivered from commercial real estate do not have the internal resource to manage specialist property investments.

However, by investing in a fund, they benefit from the knowledge and expertise of an experienced fund manager, who will take the responsibility of seeking out profitable investment opportunities on their behalf. Importantly, by investing in a fund, the aggregated overall investment is much larger, which allows for a greater range of opportunities than investing directly in a single asset on your own, and also offers diversity of specific risks.

Greater income certainty

To achieve strong returns, fund managers invest on behalf of a number of charities enabling them to compile a portfolio of many properties. The diversity of specific risks prevents investors from having “all their eggs in one basket”. This portfolio effect contributes to greater income certainty through investing in the three principal real estate sectors (industrial, retail and offices) with the ebbs and flows of the relative performance of these sectors balancing returns more consistently.

Similarly, a portfolio containing assets in diverse locations ensures that the charity investor is not wholly dependent on the performance of a single geographical location for attractive returns. Through targeting multi-let properties the level of tenant diversification is more extensive and there are multiple opportunities for the rental income streams to be asset managed so as to grow the income and enhances the capital value of the properties. Asset management serves to mitigate the impact of a weak market while amplifying returns in a strong market.

Quality commercial property investments if purchased directly can require large capital sums to secure them. Smaller charities which would like to access these investments may not have the necessary funds to do so on their own. However, one of the significant benefits of investing through a diversified real estate fund is that an investor can generally acquire as few or as many units in the fund as they wish.

Enabling thinking big

This enables investors with smaller pockets to think big and access quality of investments which can deliver superior returns. For investors with deeper pockets, the time, capital resource and specialist knowledge required to compile a portfolio is considerable and can be a distraction from the charity’s purpose.

When investing in commercial real estate it is important to be ever mindful of the changing demands of occupiers. For example, the impact of the internet on retail and industrial/distribution assets. We have seen some retailers fail recently while other retailers which have embraced the internet into their multichannel retailing models have performed well.

The high street retail portfolios required by retailers in the past have reduced, but out of town retail stores which serve as distribution hubs and as click and collect locations are in demand. Additionally, the increase in deliveries resulting from online shopping has seen an increased demand for industrial and distribution units, particularly to serve the last mile of deliveries. These are just a couple of trends which influence a fund’s real estate asset selection criteria and ultimately the portfolio’s performance.

Charity investors benefit from an advantageous tax position compared to other investors in relation to corporation tax, capital gains tax and stamp duty lands tax. With the support of HMRC it is possible for a diversified real estate fund to be structured so it is tax neutral for charity investors – thus ensuring the investment closely mirrors a charity investing directly in real estate.

Relatively low risk

At a time when attractive income returns are hard to find at an acceptable level of risk, diversified property funds give charities the option to invest with relatively low risk into a market with relative high returns.

These funds give charities the ability to access a market they previously thought they could not without deeper pockets, while a diversified portfolio gives charities the confidence that their investment will experience capital value growth over the medium to long term, in addition to attractive sustainable income returns today. A small amount of capital doesn’t prevent your charity’s entry to well managed and high return vehicles, no matter how small you perceive your charity’s reserves to be.

Commercial property exhibits many attractive features which, when combined with economic growth, relatively low interest rates and the general lack of supply, deliver resilient returns. Bespoke real estate funds for charity investors, which mirror a charity’s tax status, are likely to become more popular as charity finance managers and bursars, the custodians of charitable endowments, seek to invest where they can diversify risk whilst benefiting from resilient superior returns.

Choosing a charity investment manager

We’ve all been there – the item that looked so alluring in the shop window doesn’t seem as shiny and wonderful once we get it home. If it’s a piece of clothing, we can take it back to the shop. For a charity which feels short changed by its investment manager the process is not so straightforward, however. So is there a way to future proof against buyer’s remorse?

When a charity appoints an investment manager it will usually have been through a process of long listing likely candidates and asking them to complete a proposal, before inviting a short list of managers to come and present to them in person.

Ask other charities

The future-proofing starts with the long list: ask other charities for recommendations - they will be able to provide views on who they rate and why. Also try to gain an understanding of what different investment managers offer because some will be more suited to your needs than others.

For some charities, using a firm which invests in a fund (a common investment fund or other fund type) might be exactly the right solution; for others a segregated portfolio (i.e. holding direct positions in bonds, equities and funds) will be a better fit. Sometimes five minutes on the telephone, talking through a firm’s offering can save hours of wading through tenders from firms which were never going to be the right fit.

When the proposals come in, an effective way to whittle down the contenders is to think about what really matters to you. Prioritise what are the key requirements for the trustees and officers of the charity. It may be on-line reporting, trustee training, having an investment manager who is readily available to attend meetings, being treated as a "retail" client or being provided with discretionary management. Before you embark on your selection process understand what are the "must haves" and the "nice haves" and mark the proposal accordingly.

It’s pretty much a given that every investment manager shortlisted will tell you they are client centric or focused, the investment solution has been "tailored" for the charity and that all their existing clients love them. Obviously, when charities ask investment managers for two references from existing clients, they are going to be provided with cherry-picked testimonials extolling the virtues of the manager.

To gain a more realistic insight into a firm’s reputation, you are better served by asking for references (if you want them) from other charities before you start the process, rather than at the end.

The manager's responsiveness

"Client centric" or "focused" should be a given. It is more meaningful to establish how responsive a manager is to a client’s requirements and how flexible they are in their service and investment offering. This will come across in how they answer the initial proposal: have they followed the charity’s order of questions or have they simply printed out their stock response?

When it comes to mention of a "tailored" approach, it is essential for charities to understand what is meant by this. If the trustees have decided to appoint a manager "which" is not putting them into a fund, then a key selling point may well have been the idea of a portfolio constructed solely to meet that charity’s requirements.

The world of charity investment management, from a regulatory perspective, looks very different to that of a few years ago. The key regulatory driver behind this is suitability. This means investment managers have to evidence regularly that the investments they have made for a charity are in line with the charity’s investment mandate. Critically, this will include the risk profile. This seems eminently reasonable (and also links into ensuring the Statement of Investment Policy is up to date). However there are, perhaps, unintended consequences.

On the whole, investment managers will look to use an investment framework that enables them to meet the defined risk profile requirements (which will have been set at a house level) by ensuring that portfolios which have the same risk profile as one another also exhibit a reasonable degree of commonality between one another, hence "proving" suitability.

This means they will hold similar asset allocations and underlying investment positions at the core, and then the investment manager will tailor the remaining to ensure the charity’s specific mandate is met, including asset allocation ranges, income requirements and any ethical considerations.

This is not a bad thing from either perspective. It means the manager is investing in a reasonably sized list of holdings which they know well; rather than a potentially longer list which might have a long tail of small positions which are "forgotten". In addition, this approach ensures the manager meets another regulatory requirement, that of "treating customers fairly".

So how is this investment policy defined? It all starts and ends with the charity’s objectives – what is the strategic plan for the next five to ten years? This should be the template for the investment strategy. The ability of the investment manager to translate the charity’s plans into an investment strategy in a coherent fashion should be a deciding factor when the trustees review proposals and the existing relationship.

Common ingredient

There does not appear to be a secret formula enshrining what a charity wants from its investments or managers. However, there is always one common ingredient - trust. A bit of integrity goes a long way.

Consider the way in which your investment manager behaves if an issue is raised with them. Think about how you feel if something is wrong and the person you raise this with, immediately apologises and owns the mistake. Contrast this with a person who tries to brush over the error or passes the blame on. Trustees are humans too and are bound not to appreciate an investment manager who starts spewing technical jargon such as EBITDAs, WACCs and ROICs when questioned about an underperforming investment.

If the future-proofing has not worked and the charity is perhaps a couple of years into the relationship (hopefully not just a few weeks) and senses the manager is not quite living up to the initial billing and feels let down, the first question to ask is: has anything changed? Look at the three Ps: People, Performance and Perception.

PEOPLE. It is possible there has been a change in the trustee group; or at the investment manager. The chemistry on a committee (of any kind – not just charities) is fascinating. A change in a key member of the committee may significantly change the dynamic at meetings and the relationship with the investment manager.

The new member(s) of the committee may have different approaches or views, and the actual shape of the committee in terms of its thinking may have changed as a result. If this is the case, and a sense of unease is breeding amongst the trustees then it is perhaps worth getting together and exploring what has changed.

If the representative from the investment manager or support team has changed then it takes time for a relationship to develop and the charity may be uncomfortable with a new person depending on the circumstances.

PERFORMANCE. I have absolute sympathy for a charity which is concerned the investment manager is not performing well, and is agitated that the investment manager is set on a particular course of action. Nerves of steel may be required especially if at the outset the manager has emphasised a 3-5 year investment plan. However, if the charity has appointed the investment manager to manage its funds and if it has done so on a discretionary basis (which is usual), then the old saying comes to mind: "you don’t keep a dog and bark yourself".

At this point it is worth comparing the performance of the charity’s fund against peer group measures to ensure that for the same level of risk the trustees’ expectations are realistic. If the charity’s concern translates into "we have lost all trust in this investment manager", it needs to take a different course of action. It should review what it requires from its investments and seek another steward of these.

PERCEPTION. The charity may feel it is receiving poor service. It may be that the more senior representative from the investment manager has not attended a meeting recently, emails or telephone calls are not being responded to in a timely fashion, or it feels it is just not being listened to. So what to do?

Discontented grumbling

Often there is discontented grumbling but no concerted effort to tell the investment manager that it is just not up to scratch and to lay down the rules in terms of what the charity requires. Speak up. Again, how the manager reacts to your concerns will enable you to conclude whether further action is required.

Remember the charity is the client. It absolutely has the ability to take its custom elsewhere if it feels that it is not getting the service or performance it believes it should receive. The trustees also have a legal obligation to ensure they continue to receive appropriate advice.

"Sometimes five minutes on the telephone, talking through a firm's offering can save hours of wading through tenders from firms which were never going to be the right fit."

"Trustees are humans too and are bound not to appreciate an investment manager who starts spewing technical jargon...when questioned about an underperforming investment."

Being aware of the investment risks for charities

Investment managers in the charity sector have a responsibility to identify and continually monitor the risks facing the investments they look after. It is incumbent on charities, too, to be aware of and knowledgeable about these risks so they are able to ask the right questions of the firms which are managing their money. So what are the key risks that should be considered?

Market risk

Market risk is a perennial issue but the important fact is that with a long term time horizon for investment, most charities can ride through modest setbacks. Setting clear and achievable objectives at the outset is therefore crucial to avoid forced redemptions or sales of stocks at unattractive levels.

A core risk occupying the minds of charity investors lately has been around equities and capital volatility risk. Six years into a bull market it is not surprising if we have reached the “wall of worry” stage, where investors feel they cannot afford to ignore equities, but fear the future.

I still think equities have further to go but it makes sense to reduce exposure to Asia and the US, the latter being the most expensive of the major equity regions on valuation grounds and where headline earnings and share price momentum have started to deteriorate.

It also makes sense to re-evaluate individual holdings and have a preference for high quality companies with lower levels of indebtedness, strong cash flow generation and relatively greater earnings predictability. One can continue to see opportunities to benefit from quantitative easing in regions like Japan and Europe – though structural problems remain in Europe.

Of more concern is what has traditionally been perceived as the much safer fixed interest space, which has experienced a sustained and unprecedented period of strong real returns (UK government bonds have risen + 6.3% p.a. on average between 1980 and 2010 compared with -0.5% p.a. for the preceding 80 years).

Interest rate risk is probably one of the greatest risks that portfolio managers face at the moment. I do not expect all-out panic in the bond markets but rate rises (or their imminence) could build selling momentum and there is a serious risk of negative real returns.

Income risk

Is your investment strategy aligned with your commitments? Most obviously does your charity depend on the income or total income plus capital return of your investments to fund its activities? The Charity Commission now allows more freedom for you to take a total return approach but do you have flexibility with your expenditure levels if your income or total returns do not meet expectations?

Liability risk

For those with pension schemes, how confident are you of meeting your anticipated pension liabilities? This is a serious issue at the moment and one the Pensions Regulator is examining. It is concerned that charities are not giving sufficient thought to aligning their overall investment strategy, combining a strategy for the assets as well as a strategy for the liabilities. An over-reliance on just one side of the equation may raise some concern.

Currency risk: If you have a global portfolio are you happy that your manager has appropriate hedging and exposure strategies in place to exploit favourable currency movements and mitigate unfavourable ones? Typically, one should hedge the currency back to the base currency (GBP) of the portfolio to reduce the risk of adverse currency movements undermining positive performance.

Inflation risk: Inflation does not seem so threatening at the moment, but many economists fear that the price of quantitative easing will be inflation further ahead. This will affect asset allocation decisions – you may need assets that are inflation resilient.

It is also important to consider the impact of inflation on the costs of a charity. The overall headline government figure may not be representative of the true inflation costs in your particular charity and this may influence investment decisions.

Concentration risk

Is your portfolio sufficiently diversified to reduce the risk associated with a particular security (individual corporate bonds or equities), a sector (for instance, energy) or asset class (like fixed income) imploding?

If you invest in funds, it is useful to understand your aggregate exposure to an asset or asset class. Holding multiple funds does not necessarily equate to diversification if there is overlap in the underlying holdings. Equally important is the cross correlation between asset classes. A classic example is that some high yield and emerging market bond funds move in close proximity to equity markets.

Credit/counterparty risk

It is also worth pressing your manager to look at what checks and balances are in place within your investment portfolio to ensure that you are not overexposed to any single bond issuer or deposit-taking institution. An example may be if surplus cash is invested in a liquidity fund, what is the underlying structure, credit rating, size and liquidity of the fund?

Reputational risk

One word will suffice to illustrate this risk: Wonga. The Church of England’s controversial exposure to the payday loan business was through a fund. It is a further reminder to those responsible for investment decisions to be well informed and aware of the underlying investments you hold, and to consider if an ethical investment policy would be in the best interests of the charity.

A natural extension of this risk, whilst not directly investment related, is to consider the various sources of donor funding in terms of consistency with the charity’s wider objectives.

Fee risk

Finally, an often overlooked risk is that of hidden fees. Over the long term they have a significant impact on returns. Do you know all your investment management costs? Is your manager being remunerated for each transaction? Are you getting what you pay for – or still getting what you agreed to pay for – from your investment manager?

While fees should not be the primary driver of manager selection, being able to compare "apples with apples" between managers is important, key to which is understanding how fees are structured and levied.

Risks can appear daunting

Catalogued like this, these risks can look daunting. Perhaps it is easier to think of them as agenda items to be addressed with your investment manager. Alternatively the items could be included as part of a more formal periodic investment manager review process with specific questions around these areas. Remember, too, risk is not always bad. Without it there is little reward.

"...does your charity depend on the income or total income plus capital return of your investments to fund its activities?"

"For those with pension schemes, how confident are you of meeting your anticipated pension liabilities?"

Maximising the use of your charity's reserves

The financial management of charitable organisations has come under increased scrutiny during the last year and will likely continue to do so in the wake of the recent high profile collapse of Kids Company. But while the latter has dominated recent headlines with (as yet unproven) allegations of poor and cavalier financial management, other charities, including Children in Need, have faced criticism for being too conservative with their finances - the Daily Mail in particular criticising the charity at the end of 2014 for holding excess reserves.

This June, the research consultancy nfpSynergy released a study relating to charitable reserves suggesting that just one in 17 people think charities should save more than a year’s expenditure for a rainy day.

More transparency enables charitable donors to investigate most aspects of a charity’s financial health, thus reserves have become a key area of interest. High levels of reserves can cause a donor to wonder why the charity needs their money, while not enough can be a serious warning sign as shown by the high profile failure of Kids Company. So how much is sufficient, and how should reserves be managed?

Charity governance can be complex and one of the challenges faced by trustees is that reserves and investments are often points relegated to the bottom of the agenda after crucial areas like overall strategy, staffing and grant making have been tackled. Unless there are investment professionals represented on the board of trustees it’s often difficult to have a meaningful discussion about these topics. The following concepts should be helpful when developing suitable reserves policies.

Know why your charity holds reserves

Why does your charity hold reserves? The answer to this question should be learned and rehearsed. There are multiple reasons, but primarily charities hold reserves for only one reason - to ensure that future charitable expenditure objectives can be met.

Trustees are generally under a duty to balance the needs of current and future beneficiaries and the complex day to day operations of charities ranging from, for example, hospice care to nature preservation, require the ability to cover known liabilities and contingencies and to absorb funding setbacks. It’s really as simple as that.

In the complex day to day operations of many charities, spending every donation at the point of receipt would be both ineffective and irresponsible. A good example would be salary expenses for hospice nurses.

There is a clear legal basis for charities to hold income reserves. In general, trustees have a duty to ensure that the charity’s funds are used appropriately, prudently, lawfully and in accordance with the charity’s purposes for the public benefit within a reasonable period of receipt. Trustees are, however, justified in exercising their power to hold reserves if in their considered view it is in the best interest of the charity.

There is often confusion about what exactly qualifies as reserves, but the answer is similarly simple. Reserves are the part of a charity's unrestricted funds that are freely available to spend on any of the charity’s purposes. Endowment funds and restricted funds do not form part of reserves, but in practical terms the level of these funds often influences the required level of reserves.

Develop a reserves policy

Does your charity have a formal policy on reserves? Once it has been established that a charity would benefit from holding reserves, attention should turn to developing a formal policy for reserves.

There is no standard formula for establishing a suitable level of reserves, but there are a few useful questions to ask which will gently guide each charity towards an answer. These include detailed analysis of income streams versus expenditures, identification of any non-monetary assets and the speed with which these can be converted into cash and also a risk assessment of commitments and contingencies.

The answers to these questions should lead trustees towards an appropriate reserves policy. When completed, the policy itself should at a minimum cover the following:

- Why the charity needs reserves.

- The level or range of reserves the trustees believe the charity needs.

- Arrangements for monitoring and reviewing the policy.

If the level of current reserves and identified level or range are not equal, steps to achieve the desired level should be included. Finally, it’s also important to remember that it’s rarely appropriate to state an absolute level of required reserves. In reality, reserves will often fluctuate and an absolute level could inadvertently trigger frequent and unnecessary reviews. Instead, reserves are usually expressed as a multiple of monthly expenditure and the required level is often different from year to year.

Consider investing for improved returns

Is it appropriate to invest charitable reserves? The short answer is yes, reserves can and often should be invested, but a few factors should be considered before doing so. First of all, the absolute level of reserves often dictates investment options. For charities with small sums available to invest, the investment strategy is often quite straightforward involving simply an interest bearing savings account.

For charities with substantial amount of reserves, it may be relevant to divide funds between those required to cover short and long term contingencies. In any event, an analysis of why reserves are held and how quickly they may be required is a sensible starting point. Investment in non-cash asset classes offer charities the potential for higher investment returns, but it also carries a greater risk of loss.

In my own experience, charity trustees are usually conservative by nature and at times overly cautious. There is a perception that charity investments should be very low risk, when in reality charitable objectives are often greatly enhanced by the additional, longer term investment returns. Charities are often perpetual organisations with perpetual time horizons. It is therefore particularly important to protect the real value of the reserves over time by generating growth over and above the impact of inflation.

Set investment objectives for reserves

Clear and achievable investment objectives should be set for reserves. Once a decision has been made to invest some or all of a charity’s reserves, trustees should spend time formalising exactly what the charity is trying to achieve. This will be different from charity to charity, but examples of objectives would be to:

- Ensure stability of income.

- Preserve capital.

- Maximise income.

In reality, a middle road is often the preferred option.

Risk is another crucial element when outlining investment objectives. The assumption is often that risk should be avoided at all costs. However, setting investment objectives is not about avoiding risk but rather about identifying and managing it. If risk materialises and causes a financial loss for a charity, it is not the size of the loss that is most important, but rather how well trustees discharged their duties and considered the management of risk.

Unless there is significant specialised investment expertise on the board of charity trustees, it is often appropriate for trustees to formally appoint a discretionary investment manager which will take on the responsibility of managing day to day investment risk. Investment managers will work with trustees to help them understand the level of risks involved in market investments. This is important as the definition of risk may vary from manager to manager.

Develop an Investment Policy Statement

Once it has been determined that a charity’s reserves should be invested, it is time to formalise an investment policy. This policy is often referred to as the Investment Policy Statement, and it should be included alongside the policy on reserves in the annual charity accounts. In simple terms, the Investment Policy Statement states what the individual charity’s investment objectives are and how it intends to achieve them.

The formulation of the investment policy is, strictly speaking, part of trustee duties, but discretionary investment managers are often well placed to help and investment managers with specialist charity expertise are usually happy to do so.

Consider ethical risk

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) risk is an important area. Ethical considerations are very relevant when considering investment options for charity reserves. Factors such as climate, sustainability and human rights are increasingly important to charities and charity donors alike. There is growing recognition of how these factors can play both a positive and negative role for charity objectives.

Recent high profile examples of a perceived failure to consider ethical concerns include the Church of England and its much publicised investment in the payday lenders sector and revelations in 2013 that a portion of Comic Relief funds was invested in arms and tobacco.

Unless there is specialist investment expertise on the board of charity trustees, ethical considerations are often predominately the responsibility of an appointed discretionary investment manager. Most initial conversations with investment managers will include a discussion around ethical constraints, which allows trustees to evaluate the ethical research capabilities within each investment management firm.

For charities interested in implementing ethical considerations in their investment objectives, it is crucial to work with investment managers that can offer formal ethical research capabilities. An example of a high quality provider of ethical research is EIRIS. Wholly owned by the EIRIS Foundation, EIRIS is a social enterprise in its own right and works to provide responsible investors with independent assessments of companies and information on how this information can be best integrated with investment decisions.

A matter of risk and rewards

With interest rates persisting at rock bottom levels and only incremental changes expected in the next couple of years, the potential for higher overall returns and a supplemental income stream from charity reserves remains topical. For charities with significant reserves in place to ensure continuity and the successful provision of future objectives, it’s often a wise decision to accept a degree of risk to obtain improved returns over the longer term.

Trustees have wide powers of investments and as long as the charity itself undertakes a suitable review of current and future income and expenditures, and advice is sought and obtained from persons with specialised expertise in the field, risks can usually be mitigated and managed in a manner well suited to individual charity aims and objectives.

"Reserves are the part of the charity's unrestricted funds that are freely available to spend on any of the charity's purposes."

"There is a perception that charity investments should be very low risk, when in reality charitable objectives are greatly enhanced by the additional, longer term investment returns."

The acceptability of risk for charity investors

An enduring conundrum with charity investment is the relationship between the desired return a charity wishes to make on surplus reserves and the amount of risk it takes to achieve this. A popular misconception is that charities are very conservative entities, averse to taking risk. After all, the assets that are entrusted within charities are for the benefit of the public and the specific beneficiaries of the organisation. It is also true that the trustees of a charity have a duty of care over the assets of a charity. In reality, charities can take risk where it is appropriate to do so.

The Trustee Act 2000, the legislation relating to the investment powers of trustees, states that trustees have a general power of investment. When making any kind of investment for a charity it should be made as if the trustee were absolutely entitled to the asset of the charity. Provided an investment is deemed suitable for a charity and there is appropriate diversification of assets, trustees have a wide choice of investments they can employ to meet the charity’s objectives. The trustees make the strategic investment decisions for the charity as they arise and should review this on a regular basis.

Charities share some attributes with pension funds; both are regulated and have an obligation to meet the needs of current and future beneficiaries, but there are also a few significant differences. While pension funds have defined liabilities relating to the age and pay-out of the pensioners, charities are mostly around for a very long time or in perpetuity. They have a very long term investment horizon and while they do not have defined beneficiaries, charities which have surplus capital will wish to protect the real value at least in line with inflation over time. Therefore an investment into real assets, such as equities and property that participate in the real economy, is likely to achieve the need to have sufficient funds to meet their long term charitable objectives.

Length of service

Having established that charities are long term investors and prepared to invest in risky assets to achieve their aims, consideration needs to be given to the trustees. While certain charity governing documents do not specify the length of service of a trustee, increasingly they are appointed for a given period, usually a set number of years. As previously noted, while trustees have a duty of care, they also have a duty of prudence and should take special care when investing the funds of the charity. Trustees should avoid undertaking activities that might place the charity’s endowment, funds, assets or reputation at undue risk. It is therefore not uncommon for trustees to have a lower risk attitude while they are serving the charity as they "do not want anything to go wrong on their watch".

The duty of prudence extends to taking advice on investments. Unless a trustee is appropriately qualified to make the investment decisions or reasonably concludes that in all the circumstances it is unnecessary or inappropriate to do so, they must obtain and consider proper advice. It is therefore reasonable to conclude that trustees will revert to a smaller number of well-known charity advisers rather seeking guidance from alternative sources that might produce a better outcome. As the saying goes, nobody ever got fired for buying IBM!

The contrast between the long term horizon of a charity and shorter term behaviour of a trustee has been covered by a new study into charity investment. This involved a survey of UK charities with between £1 million to £50 million in investable assets. The study showed two in five (41%) charities were concerned about their performance over the next 12 months, reflecting short term financial concerns and typical trustee behaviour. As a result, charities were focusing on risk when managing their investment portfolio. Indeed, two thirds (62%) of charities believed risk was the most relevant metric when managing an investment portfolio, while a third (33%) cited return and just 7% stated it was yield.

Investment in equities

Notwithstanding market falls in 2000 with the dot com bubble, the credit crisis in 2008 and despite current global economic uncertainty, charities continue to invest in equities to deliver effective market returns. Over four fifths (81%) of charity portfolios said they were invested in equities, with bonds and property equal second (56%). It is notable therefore, that despite increasing levels of market volatility, the majority of charities remain allocated to equities. This underlines their long term investment horizon and the fact that trustees in general view equities as medium risk, while financial regulators regard them to be more risky.

Interestingly, while charities are happy to invest in equities, more than two in three (69%) charities target "inflation plus" return for their investments with 38% targeting a combination of market indices.

An inflation based return requirement aims for both the capital and income to rise at least in line with underlying inflation (either Consumer Price Inflation – CPI or Retail Price Inflation – RPI). The "plus" factor accounts for investment management fees or any other frictional cost of investing and is the amount by which the investment manager is expected to demonstrate outperformance. As many charities employ staff and need to keep in pace with wage inflation, RPI is often seen to be a more appropriate measure. It is usually measured over a rolling timeframe, typically 3 years. By adopting an inflation based return requirement, the overall portfolio of investments can be relatively unconstrained by the type of assets that are employed to achieve the aim.

Investment performance reference

Targeting a combination of market indices or using a market based benchmark as a reference for investment performance makes sense if a charity is prepared to take more risk. This typically is a composite of relevant market indices, such as the FTSE All Share Index (UK equities), FTSE All Stocks Gilts Index (sterling bonds), MSCI World Index (global equities), etc. Depending on the required risk/return requirements of a charity, a benchmark is constructed from different market indices to measure the relative return of the underlying investment portfolio. A natural concurrence of this approach is that the underlying investments made by either the trustee or their adviser will be more constrained to match the indices that they are measuring performance against.

As a result, this constrained investment approach is likely to result in a charity holding assets in both rising and falling markets, making overall portfolio returns more volatile in the short term. Three quarters of the charities surveyed use a markets based benchmark to compare investment performance and just under half (44%) of charities said they use an absolute based benchmark, such as inflation, LIBOR or cash.

The fact that 62% of charities believe risk is the most relevant metric when managing an investment portfolio is telling. There are a number of factors that possibly underlie this statistic if we look beyond the obvious duty of prudence. Trustees are becoming more understanding of the relationship of risk and return. As charity investments get ever more global in outlook, investing in multiple asset classes, having an appreciation of the relative risks being taken is important.

Charity investment managers are more open with risk and are displaying various measures of risk in their regular reports to trustees. The increase in use of investment consultants and charity peer group indices has extended the focus on risk based investment returns, with the likes of asset risk consultants now producing regular analysis of risk orientated charity indices for the UK charity market. These factors are enhancing a trend towards analysing risk factors and it is likely that charity trustees also are getting savvier with their investment decisions.

Low return environment

The fact that 41% of charities are concerned with their short term performance is also a reflection on the current low return environment. Charities which have a relatively high return or income needs have to take increasing levels of risk in a low interest rate world. As investors chase investments for income, typically government bonds or treasury stock with excessively low yields and shares in expensively priced companies paying a higher dividend yield, charities run the short term risk of capital loss if interest rates rise. In these circumstances, charities are likely to be more reliant on their endowment investments to meet the ever present requirement to balance the needs of current and future beneficiaries.

Returning to the long term investment nature that charities display, combined with trustees´ duty of care and prudence, provided a charity has sufficient short term cash to meet ongoing capital expenditure and liquid reserves to meet likely charitable expenditure for the next 6-18 months as appropriate as part of a sensible reserves policy, longer term investments can and should be put to risk. The need for short term liquidity caught some charities in 2008/09 during the credit crisis. For example, larger US endowments have historically bought illiquid assets such as physical property and private equity investments for long term capital gains.

Not only did Harvard and Yale endowments witness portfolio declines of -27.3% and -24.6% respectively, they became forced sellers of liquid assets to meet short term funding needs. Of course, these endowments have recovered their market values since that point, but it highlights the need to have sufficient liquid assets to balance the longer term higher risk attitude.

Other risks that charities and their trustees need to consider include reputational risk, investing in areas that might have a negative impact on the donors or beneficiaries of the charity. High profile examples - such as the BBC Panorama programme’s exposé of Comic Relief’s investment in the shares of tobacco, alcohol and arms firms - have caused charities and trustees to take more care when making investments that may contradict their core values.

Prudent governance requirement

In conclusion, charities need to be prudently governed. Trustees need to have considered the relevant issues in making investments, taken advice where appropriate and reached a reasonable decision. Provided they make provision for short term spending needs, trustees are unlikely to be criticised for their decisions when adopting a particular investment policy in meeting the long term investment requirements of the charity, and fundamentally take risk where it is appropriate to do so. The Charity Commission’s guidance on investment, CC14, offers detailed information for trustees to follow.

"...two thirds...of charities believed risk was the most relevant metric when managing an investment portfolio, while a third...cited return and just 7% stated it was yield."

"...this constrained investment approach is likely to result in a charity holding assets in both rising and falling markets, making overall portfolio returns more volatile in the short term."

"...provided a charity has sufficient short term cash...and liquid reserves...longer term investments can and should be put to risk."

Fund managers keeping to their principles

Charities using fund managers will be taking decisions at some time whether to stay with the managers or find alternatives. I hope this article will help them with their thinking.

As investors employing a multi-manager approach, we are often asked about what would lead us to sack a manager. In reality, there may be a number of reasons, ranging from non-manager related ones such as asset allocation decisions or corporate developments, to more manager-specific reasons.

Let us focus on the latter, as these are more representative of the challenges that we face when performing our role. Given only a word to describe the most likely reason for terminating a manager, it would be “drift”. Given the luxury of three words, I would go for:

- Well

- Endowed

- Lemmings

Let me explain the one word answer in more detail, as this should help any readers still grappling with the three word version.

Initial investment decisions

When looking at fund managers’ investment processes, it quickly becomes clear that a lot of thinking – and even more effort – tends to go into initial investment decisions. Regardless of their universe, managers usually have, or at least pretend to have, some sort of screening and filtering process that helps them narrow their opportunity set down to a manageable size. Thereafter, they conduct more thorough due diligence on the candidates which made the shortlist, and eventually populate their portfolios according to their risk tolerance with those which made the final cut.

I must have met over a thousand different investment teams since I started doing manager research and selection, and I have to admit that very few could not articulate clearly what their own selection process was.

But then the main issue we face is not the inability of managers to describe their process. Indeed, most of them now have a deck of slides and a few good examples to hand anyway. The role of the slides is to remind them of what it is that they say they do, and the examples are to prove to whoever may still be in doubt that the process works.

Rather, the main issue is that more often than not we discover that there are times when managers do not follow their own processes and philosophies as diligently as they say they do or, even more worryingly, as closely as they believe they do.

The main symptom of this naughty behaviour is seeing “process non-compliant” stocks make their way into portfolios. That this tendency is particularly prevalent in the aftermath of a spell of poor performance is particularly noteworthy.

This phenomenon can be described as “process drift”. There are many directions in which a process can drift, but a particularly common occurrence is for underperforming investment teams to add to their portfolios names which have performed strongly and are widely held by their peers.

Excuses for the inclusion of these “impostors” range from claims that the positions are “only there to reduce risk” to suggestions that “careful inspection will reveal the holding to be fully aligned with our process”. An extreme example of this behaviour, in this case taken from 2012, was the inclusion in the portfolios of so many global and US equity managers (some of whom did not even have the US in their benchmarks) of shares in Apple Inc., regardless of their investment style.

Lemming-like behaviour

For responsible fund selectors, such lemming-like behaviour should immediately raise a red flag. Not only is the act of piling into a stock after it has had a period of strong performance likely to lock in some of the fund’s relative underperformance against the peer group, but it may also lead to “style drift” if a sufficient number of such names make their way into the portfolio. Speaking for our own process, I can state without hesitation that the faintest whiff of a lemming will take us close to a sell decision.

Our other main concern does not relate to names entering a portfolio. Rather, what keeps us awake at night is a combination of what is not in a portfolio, or what should not be there. In other words, managers are often as guilty of buying what they shouldn’t buy when it’s doing well, as they are of not selling what has not done well after they’ve bought it.

This behaviour, also called the “endowment effect”, leads to another very alarming drift in the investment process: “thesis drift”.

Behavioural scientists describe the endowment effect, also known as “divestiture aversion”, as the hypothesis that people ascribe more value to things merely because they own them. This is illustrated by the experimental observation that people will tend to pay more to retain something they own than to obtain something owned by someone else – even when there is no cause for attachment, or if the item was obtained only minutes ago.

Sticking with positions

In the field of investment management, this phenomenon occurs when managers are unwilling to close a position after the market or news flow goes against them, and they instead invent – or convince themselves of – a different or new reason to stick with it. Again, this behaviour was especially prevalent as the Apple Inc. stock price started to drop at the end of 2012. From being a fantastic opportunity, all of a sudden it was there for risk control vs benchmark.

This type of behaviour can also be observed in respect of underweight positions. Take current fund management consensus on Chinese banks, for example. For the last few years Chinese banks have been pointed to as as the thing not to hold in your portfolio. Indeed, I can only think of three managers who do not have a large underweight in the sector, and of these two have only a neutral weight and the last one just a timid overweight.

Most managers have been very vocal on their reasons for not holding any Chinese banks, citing opaque books (which is perhaps ironic given what we all learned about the developed world’s banks in the global financial crisis), the emergence of a credit bubble, and fears about the implications of the murky and unregulated world of the Chinese shadow banking system. Some managers have even pledged never to own a Chinese bank stock.

Most managers have done very well with this position, or at least had done very well until a few months ago. Very few of the managers I speak to are willing to move to a neutral position, or even take profit on their underweight position. When pressed, they do admit that the sector does now look attractive but they feel happier being “safely underweight” like all their peers. Naturally, having been so vocal about their dislike for the sector, none are keen to be seen as the first one to move in.

Australian sugar ants

To borrow another analogy form the animal kingdom, this kind of behaviour is rather like that of Australian sugar ants. Like most ants, these creatures navigate around their universe by following pheromone trails left behind by others ants. An interesting phenomenon occurs when enough of them lose track of the scent; they begin to follow the ant immediately in front, leading to the formation of a huge ant spiral.

The poor things then become trapped in this spiral, marching pointlessly around in a loop, probably comforted by the false assumption that “someone immediately ahead must know what they’re doing”. They continue in this manner until finally they drop dead (conceivably close to a rotting Apple).

The 18th century French author Philippe Destouches once said “la critique est aisé mais l’art est difficile”. Roughly translated, this means “it is easier to be an art critic than an artist”. Hence, as a fund manager involved in manager selection it is critical for me also to sidestep the traps I hope my managers can avoid. I have made sufficient controversial and contrarian calls in my career (some with glorious outcomes, and a few others I will never forget but would rather not be reminded of) to know that I am unlikely qualify as a lemming.