CHARITY INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT RELATIONSHIPS

How responsive should charity investment strategies be?

FROM THE EDITOR: The aim of this feature is to focus the minds of charity trustees and charity finance directors in particular on how they should plan for the possibility or respond to the actuality of investment markets turning severely downwards after long, sustained rises and to what extent a long term charity investment strategy should have flexibility built into it to deal with turbulence and more than short-lived movements in the other direction.

Just how long should the nerve of a charity investment committee be expected to hold when a market goes in the wrong direction? When is the point that the investment adviser should accept that the charity could have difficulties in sticking with the strategy, e.g. because of a variety of financial pressures coming together? How should investment advisers and charities be working together to address the problem of unexpected sustained market downturns?

We have six contributors who answer these questions in their own individual ways below. They are: Charles MacKinnon of Thurleigh Investment Management, Kate Rogers of Cazenove Capital Management, Adrian Taylor of Smith & Williamson Investment Management , Mike Goddings of Ecclesiastical Investment Management, Tom Rutherford of JP Morgan Private Bank, Christian Flackett of investment firm GAN, and Patrick Ghali of hedge fund advisory company Sussex Partners.

Please scroll down to see each article.

Establish what you are trying to do

CHARLES MACKINNON of THURLEIGH INVESTMENT MANAGERS comments: All charities owe their foundation and genesis to a perceived shortfall in society’s provision for some general need. This need may be very broad, for example provision of care for the elderly, or very specific, such as providing medical care and support for very premature babies.

It is the nature of this charitable aim that generates tension for the trustees in their choice of investments. A well known example is that cancer charities may not wish to invest in tobacco companies, on the basis that the products of these companies are, in part, the cause of the ills which the charity is seeking to cure. This tension has to be balanced with the need of the trustees to provide the best possible outcome for the largest number of possible beneficiaries.

It may be that by rigorously eliminating tobacco and its associated products and services from your portfolio, you so savagely reduce the investment outcomes that the charity is unable to perform its basic charitable aims.

Leaving aside the conflicts of how to invest, there is also the conflict of whether to invest at all, or to invest now. This is where the relationship between the head of the charity, the head of its investment committee and its investment manager is of paramount importance. For most charities there is an almost infinite call on their resources, but there is only a finite amount of return that can be extracted.

As part of the budget process a charity needs to include a detailed projection of likely, best and worst case outcomes from its investment portfolio. This set of possible outcomes should then be strictly attended to when making commitments for future spending, and if this is done, then the whole process is much more resilient to the vagaries of the market.

Recent market movements have highlighted the need for a responsive strategy, with two boom and bust cycles since 2000, and most importantly very low interest rates on cash and short dated bonds over the recent five years. If a charity had held its assets in cash over this period it would have suffered a significant diminution in its ability to perform its charitable aims.

This is where the relationship between the charity and the mandate it gives its investment manager is of paramount importance. The charity has to first establish what it is trying to do in financial terms as opposed to in social terms, and then it must relay this to the manager who may say that the aims are not achievable in the market.

For example, it is not possible to provide a guaranteed return of 10% on your money with no risk to capital in the current market environment. So, if you as the head of a charity want a 10% annualised return, you are going to have to accept some risk to capital, and some variability in the timings of that return.

CHARLES MACKINNON of THURLEIGH says: So what to do today? We have record low interest rates in the UK and the USA, and equity markets have recently once again scaled new highs in nominal terms. If you, as a cautious charity have been sitting in cash for the last five years you have suffered a massive opportunity cost, but should you start to commit capital to the market today? If you, as a well endowed and mature charity have been fully invested and have enjoyed the significant returns from recent equity market rallies, should you be stepping away?

The answer is the same for both: work out what your obligations are, and then work out what you would like to do but will only do if there is funding, and establish a time frame for these aspirations. What you should not do is take a view on the future direction of interest rates or equity market returns, and building your budget around those views.

Invest long term and change infrequently

KATE ROGERS of CAZENOVE CAPITAL MANAGEMENT comments: Beware of the phrases "things are different this time" and "new paradigm". We go in cycles, what comes around goes around. History has a habit of repeating itself. Charities as long term participants in society should not be phased by the endless oscillations. A bit like the experienced grandfather figure, we've seen it all before.

Charity investments exist to help charities further their mission. As reserves, in case of fluctuations in income; or as foundation or endowment assets, generating income to spend on their charitable aims.

Charity investment strategies should be designed for each individual circumstance and should be framed by the ability to tolerate volatility in capital value and the charity’s investment time horizon. Reserve assets tend to have a lower tolerance for moving values and a shorter time frame when compared with foundations and endowments. These are the real grandfathers of the charity investment world.

It is these assets which represent the bulk of charity investments. These charities have very long term time horizons, often with an aspiration for perpetuity, or eternal life. Investment strategies can take a very long term view, giving charities a distinct advantage over other investors such as private individuals or pension funds, who have shorter time frames or defined liabilities. As the adage says, everything comes to he who waits.

So am I proposing a lack of action in charity portfolios? A long term buy and hold strategy? No. I am suggesting that investment strategy should be set with the long term in mind, but I would encourage regular review. Strategy, in investment terms, can be defined as the long term asset mix that best meets the needs of your charity as expressed in your written investment policy.

This should not be changed regularly, unless there is fundamental change either in your own circumstances or in investment markets.Which brings us back to the original question: how responsive should charity investment strategies actually be?

I would argue that the definition of a "fundamental change in investment markets" is at the heart of answering this question. Where the investment world changes fundamentally, charity investment strategies should be rewritten and asset mix changes may be significant. A fundamental change is one that is likely to be permanent, or at least secular not cyclical, i.e. multi-decade not multi-year. One that is factual, not subjective or based on expectations.

An example in recent history might be the broadening of asset classes available to charities over the last two decades. As the number of pooled funds in alternative asset classes - property, commodities, private equity, absolute return - increases, so does the choice for smaller charity investors and the ability for diversification within investment portfolios.

Charity investment strategies should be very responsive to fundamental changes, which should provoke a reappraisal of long term strategy. In addition, a charity investment portfolio should be able to be responsive to shorter term changes in markets, and should have the flexibility to reflect the views of the investment manager and the trustees.

These more subjective views are inherently more uncertain, and the extent of their expression within portfolios needs to be controlled so that a wrong move doesn’t derail the entire long term strategy.

In a period of down equity markets it can be difficult for trustees to stick with a long term investment strategy, but it is also notoriously difficult to time markets. Just as trustees may wish to reduce their exposure to equities in down markets, they will wish to increase exposure in better times. Missing the best 10 days in global equity markets (MSCI World) from 2002 to 2012 was the difference between a return of 69% fully invested, and a return of -5%. It is time in the market, not timing the market that generates returns.

KATE ROGERS of CAZENOVE says: I would advocate charities adopting a strategy and staying the course. The governance of this can be improved by determining worst case scenarios, allowing trustees some comfort that, within a certain range, a period of negative equity returns is a "normal" market event.

So use your position as a long term investor to your advantage. Decide on an investment strategy that best meets your aims, and stick with it. Review regularly, change infrequently and only based on fundamentals. Respond to shorter term market movements to take advantage of opportunities, but do it in a risk controlled manner in order to avoid jeopardising your long term strategy. And don’t panic. Short termism can be a significant detractor to long term value. Unless, of course, it really is "different this time"

Putting investment decisions into a structure

ADRIAN TAYLOR of SMITH & WILLIAMSON INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT comments: Finding a universal investment strategy which is suitable for every charity, and which is unaffected by possible market volatility, is extremely difficult. Each investment decision is unique to every charity and should be considered using three key steps.

First is to set the investment objectives. For this, the trustees should address the charity’s aims as defined in the governing document or scheme, and be prepared to regularly review those objectives.

Second step is to consider risk. Defined in several ways, such as fluctuations in capital and income values, the level of risk to achieve the required return should be agreed by the trustees. They also need to consider the investment timescale which may help to iron out any short term market volatility.

The Charity Commission encourages trustees through its investment guidance notes (CC14) to give significant attention to these issues. These guidelines may help trustees to address a question frequently heard: “After a strong performance in 2013, and given an uncertain global background, should we be seeking protection against a sudden downturn?”

This leads to the third step of assessing the investment outlook. With the future often uncertain, investment managers emphasise the importance of advising charities on the most appropriate solution to match their objectives and approach to risk taking.

In today’s market there is an array of assets available to meet most charity investors’ needs. These include bonds and alternative assets, offering different market characteristics from equities, which can help to deliver smoother, although potentially more modest, investment returns.

There are also synthetic structured products and other derivative instruments, which aim to provide an element of downside protection. However, these may incorporate a capped upside, meaning gains could be restricted if assets rise beyond set limits.

While not possible to control the exact investment outcome it is, of course, feasible to build a portfolio of assets to accommodate a range of probable outcomes and which is in line with your risk/reward requirements. This strategy may need to take into account other factors such as the unwillingness to accept a drop in income, or a fall in capital value, as both may be necessitated in the short term. Alternatively a five year investment strategy will mean that you hold fewer concerns about any short term market volatility.

It is important to maintain flexibility as even a long term strategic investment approach should include the ability to take advantage of short term anomalies or cope with sudden significant setbacks.

The benefit of this approach can be shown through the example of BP, the UK-quoted stock. Until the Gulf of Mexico disaster in April 2010 it represented 8% of the FTSE All Share Index providing 15% of the index’s total income. It was a popular investment with an attractive and consistent income and growth record.

The disaster saw a dramatic fall in share price and a temporary suspension of its dividend which impacted many investors’ income streams.

Those with a diverse and flexible investment strategy may have chosen to sell and invest the proceeds in alternative income stocks and then repurchase BP when confidence returned. Others would have looked to buy on weakness.

Both approaches can have merit and depend upon the trustees’ attitude to risk and reward. It also shows the importance of ensuring that a proportion of the charity’s assets are sufficiently liquid and not tied in for the long term, so that it can respond to unforeseen situations.

This also highlights that while a good stock selection in a portfolio is helpful, a full understanding of the objectives and a risk assessment are necessary to achieve appropriate results.

ADRIAN TAYLOR of SMITH & WILLIAMSON says: This is where a strong relationship, including regular communication, with your investment manager is important, particularly at times of market volatility. They understand the investment outlook and can assess how the probabilities associated with a range of portfolio structures can meet your needs. This should provide for an appropriate investment solution in an uncertain and challenging investment environment.

The trustees must also clearly understand their charity’s investment objectives and ensure there is a strong correlation with the charity’s investment strategy. They have to review regularly their investment strategy and ensure that it remains appropriate, particularly in times of in changing markets.

In reality there is no perfect solution. While predicting the future is difficult an efficient investment strategy should combine a careful analysis of your objectives and requirements over risk and return, while drawing on the skills of an investment adviser.

Getting the investment management agreement right

MIKE GODDINGS of ECCLESIATICAL INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT comments: The noughties were a fraught decade for charities from an investment perspective, with an unusually high number of severe market downturns. Consequently, many new investors will have learned to their cost that timing and duration of investment are as fundamentally important as asset allocation in determining returns.

Not only was it a decade of unpleasant surprises for capital values, for existing investors, it was also one in which it was a struggle to recover lost income resulting from Gordon Brown’s clunking fist punching a 20% hole in equity dividend distributions by removing advanced corporation tax credit.

And since then, heightened volatility has become the norm.

In determining whether and how charities should respond to changes in the market, it is worth highlighting the differences between private investors and charity trustees. Private investors are not bound by charity law; they are able to make decisions in isolation rather than by committee, and as a result can invariably react more quickly.

The degree to which charity trustees can exercise any kind of responsiveness to market conditions will also depend on the type of arrangement they have with their investment manager. Very few managers now facilitate advisory agreements under which trustees can seek advice, and then choose whether or not to act on it. However, this really is the only way that rapid decisions – rightly or wrongly – can be made in the face of changing circumstances.

Most investment managers will operate under a discretionary mandate which enables them to manage the money as they see fit. Risk will often be controlled by asset allocation, with the manager free to move within predefined bands. It is therefore vitally important to ensure that this agreement defines the level of risk or volatility that will be acceptable, and review this in the light of any change in the charity’s circumstance rather than as a reaction to adverse market conditions.

Those charities investing in funds with no encompassing management agreement need to look closely at how they have performed in bear markets. Whilst past performance is not guaranteed to be repeated, it is none the less an indication of how the manager reacts to changing circumstances. For that reason, it is also important to establish whether the same manager is still in place.

The importance of getting it right from the outset – rather than panicking at the first sign of trouble – cannot be overstated. The investment management agreement is there for this purpose, and reputable fund management firms use independent sources to calculate volatility or other measures of risk.

Contrary to popular belief, even the best investment managers cannot forecast the severity and duration of a market downturn, and certainly cannot predict it precisely in advance, so any decision to move out of higher risk assets may be like shutting the stable door after the horse has bolted. Although this may be appropriate if the charity’s circumstances have changed to the extent that further capital losses cannot be tolerated, a simple knee-jerk reaction to continuing bad news may have negative implications for future beneficiaries.

Realising or seeking to cap an unrealised loss by sheltering in a temporary safe haven can pose problems. Ultimately, a decision has to be made to continue the journey towards future capital and income growth when the weather forecast predicts it is safer to venture out into riskier waters. However, the point at which markets revert to positive returns is equally difficult to predict, as is the rate at which they accelerate. The probability of bailing out of a falling market and re-entering it on the rebound at a lower point than when it was exited is inevitably quite low, and can often mean the value of the portfolio will have been eroded for no reason.

MIKE GODDINGS of ECCLESIASTICAL says: Although a market fall of 20% sounds scary, selling 100 shares for 80p simply because they were originally worth £1, and then having to buy them back for £1.10 after the initial rally means you end up with only 73 shares worth £80 instead of 100 shares worth £110. And if each share was producing a dividend of 10p per share, not only have you forgone that income for the time spent sheltering from the storm, your new income will be £7.30 instead of £10 – a 27% reduction when your obligations to future beneficiaries are likely to have increased, therefore further widening the gap.

This is clearly an overly simplistic example, as it takes no account of any gains or losses made whilst sheltering in lower risk assets, nor does it include the costs of sale and purchase, all of which have the potential to improve or worsen the outcome. It does however highlight the advantages of being able to take a longer term view by looking across the valley to the hills beyond, and reinforces the importance of getting the groundwork right.

Focus on risk rather than timing

TOM RUTHERFORD of JP MORGAN PRIVATE BANK comments: There are many good reasons to invest in equities over the long term. As we pass the five year anniversary of the nadir of the crisis – at least in stock market terms – so many will rejoice about the upwards trajectory and a lately improved economic outlook. However, such are the memories of the financial crisis of 2008-9 that others will reflect on the cyclical fragility of markets and hope they are better positioned to cope with any future pronounced downturn.

Of course the charity investment market is a diverse realm so it is perhaps unrealistic to suppose that one size will fit all when it comes to gauging the right level of sensitivity that should be shown. The sector displays huge disparities of wealth and income, seeking to satisfy an equally bewildering array of objectives over very different timeframes.

A lucky few will cite an investment time horizon of many hundreds of years and will bias their endowment asset allocations in favour of riskier assets claiming not to care for the bumps and dips along the road. This institutional thinking borrows from the norms of pension fund investment management, in particular, and provides an academic rationale for onboarding few defensive shifts on a short term tactical basis.

However, this approach was seriously tested during the depths of the recent crisis in the spectre of financial Armageddon and trustees need to be sure about their fiduciary obligations to adopt this line.

It is beyond the infrastructure and capabilities of most charities, indeed of many advisers, to time markets precisely and so it is unrealistic to place too much expectation on this approach.

Portfolio construction experts will cite statistics suggesting that over three quarters of long term returns are driven by strategic asset allocation – i.e. the mix of cash, equities, bonds, commodities, hedge funds, property and private equity in any portfolio. The less liquid of these are the preserve of larger portfolios and are not suitable for all charities.

Yet protecting the value of assets during prolonged market downturns does give a powerful compounding effect to long run returns, so some degree of tactical awareness is warranted. Adept advisers will weight portfolios towards or away from riskier assets as the environment suggests. Here a discretionary investment framework offers greater utility understanding that constraints and limits to activism will apply.

Speaking to the usage of hedge funds and structured products specifically, many trustees are hesitant towards such strategies which can serve to reduce overall portfolio volatility and protect capital value during times of market stress. These absolute return orientated mechanisms are usually expensive by comparison to traditional “buy and hold” approaches and often beyond the comprehension of the lay members on the board.

Understandably the less financially savvy may veto such mechanisms. Yet this may import downside risk through reliance on a narrower set of assets or, worse, a misplaced sense of protection through investing in line with observed peer group practice.

Cue a well meaning yet circular discussion as to which risks are appropriate for charities. Simply put there is no clear answer and behind all assets lurk potential dangers: developed equity markets contend with all time highs and uncertain sentiment, while emerging markets reflect the inevitable worries of an uncertain geo-political backdrop; bonds carry duration risk in case rates suddenly increase; and hedge funds and structured products designed to protect value during times of weakness carry illiquidity and issuer default risk. All the while inflation washes away the real value of cash balances.

The point here is not to scaremonger charities away from investing altogether, rather to identify that different asset types assume different forms of risk. With this in mind there is utility in trying to calibrate acceptable levels of risk, and not just expected levels of return, when determining the optimal asset allocation over the long run.

TOM RUTHERFORD of JP MORGAN says: So, if a charity is most concerned about realising its assets at times of stress, then illiquidity and investment default risk may be of greater concern to them. Whereas those more anxious for the nominal loss of capital value – whether or not realised – might have greater concerns for the extent and nature of their equity exposure, potentially increasing exposures to hedge funds or structured products. Those with longer term horizons might not share such worries as explored above.

Those with less income dependency to fund operations may seek to build up cash levels to deploy capital opportunistically at better entry levels as much as a pre-emptive defensive tactic. And so forth.

Both charities and advisers have a duty to think about the likely and possible scenarios and to build their investment portfolios accordingly. Here trustees can help their advisers by clearly stating their priorities so those advisers can think around these specific risks allocations within the portfolio. Within a plural sector different styles and strategies will work better with different charities. Thinking through scenarios works well for all.

Flexibility to absorb short term market strategies

CHRISTIAN FLACKETT of investment firm GAM comments: Charity finance directors and trustees face a complex task in ensuring that they can effectively fund current activities and campaigns, while safeguarding assets for future plans and projects. The sustainability of charities’ business strategies depends on their ability to protect and grow assets throughout the market cycle. This requires taking a long term view, and knowing when to stick with your original strategy despite short term volatility.

Charities must plan for the possibility that the market could experience a downturn after a period of impressive growth following the global financial crisis. Investment strategies must therefore have the flexibility to absorb short term market swings.

Most charities do opt for a diversified portfolio to help protect against market moves - even if equities are at the heart of the strategy. If the portfolio is truly diversified to include non-correlated asset classes, one can reasonably expect a meaningful cushioning of any blow should equity markets suffer a large and/or sustained period of turbulence.

Now that permanently endowed charities can adopt a total return approach without seeking Charity Commission authorisation, trustees are able to include less yield-focussed, non-correlated asset classes such as credit long/short or macro-focused funds.

However, equities remain the most effective way to monetise human ingenuity and deserve to be at the heart of any well-diversified portfolio. 50% in the equities of the portfolio (the growth book) and 50% in non-correlated assets (the capital preservation book) is a useful starting point. This does however vary from case to case – each charity is different and has requirements unique to it. Even a 100% equity portfolio may potentially be appropriate for a charity with a very long time-horizon and no near term funding requirements.

When markets dip past experience tells us that trustees should hold their nerve and ride out the volatility as equity markets tend to regain their losses, even if it takes some time. Capitulating in a trough will only lock in the loss. Non-correlated assets should, however, provide some relief in the meantime.

One of the first things would-be investment managers are taught is to establish the risk profile of their client. As part of this process, the investment manager should ascertain what level of volatility the charity trustees can stomach and make absolutely clear what can happen in a realistic “worst case scenario”, for example a 50% correction in equity markets.

Take for example a charity with a 100% equity portfolio. Then imagine a period of severe equity turbulence which the trustees react to by selling out when the endowment has lost 50%. You can only conclude that the investment strategy was not suitable in the first place for this charity and a more diversified portfolio should have been agreed.

Investment managers must work closely with charity trustees to explain the process of investing. One method which is very effective is regular educational seminars. These should not be events where asset managers sell their services, but rather where they educate trustees on what they can reasonably expect from an investment portfolio.

CHRISTIAN FLACKETT of GAM says: Charities have a right to timely and open communication from their appointed investment managers on the opportunities, dangers and implications of the current investment environment. Portfolio review meetings should ideally be held every six months (and at least annually) to ensure that investment strategy and asset allocation remain suitable. There should be at least two portfolio manager contacts at an investment provider who are well known to the trustees and are available for contact at any point.

Both parties must be cognisant that circumstances can change (for example if a charity which previously required income now needs a more aggressive growth strategy) and it may not be appropriate to wait until the next scheduled review meeting to instigate a change. Some flexibility should always be retained.

One of the key messages is that a carefully constructed diversified portfolio is likely to give you a higher unit of return per unit of risk (a higher Sharpe ratio) and should dampen those peak to trough falls considerably. A diversified portfolio is therefore likely to provide the most sustainable, least volatile returns over the long term.

Charity trustees and finance directors could face considerable financial pressure should portfolios continue to underperform over a sustained period of time, but in most instances they should stay the course. Regular interaction with investment managers is key to understanding recent performance and planning to ensure a strategy remains sustainable. Trustees should avoid making rash investment decisions and have the patience to wait for returns to recover after volatile market episodes.

Hedging out large swings for charity investors

PATRICK GHALI of hedge fund advisory company SUSSEX PARTNERS comments: With the current bull market in equities in its fifth year, many charity boards and investment managers are asking themselves a) should we be more aggressive in our investments to avoid criticism for underperformance, b) should we reduce our exposure to risk, as the bond markets seem to be nudging the bear and every pundit states that stocks cannot continue their feverish pace?

These questions are facing every charity, endowment and pension fund. We have arrived at the proverbial “rock and a hard place”. While many equity markets hit new highs, the China slowdown is worsening, emerging markets currencies are in crisis, and the situation in the Ukraine is suggesting the commencement of a 21st century cold war, with tariffs and embargoes to follow, resulting in economic losses all around. What to do?

In general, but especially in times like these, we feel that there are some basic investment truths that any charity investor should try to remember. They include the benefits of diversification, targeting risk adjusted returns net of all fees, and establishing a balanced risk/return profile to a conservative degree in order to compound positive returns over long periods of time.

But more important than the above is the individual you chose to pursue these aims – the identification of a proven, top performing portfolio manager. Then, let him do his job, in good times and bad.

The fundamental issue is that the majority of paid professional investment managers underperform their respective indices. A recent study in the US compared the returns from 1997 to 2012 of a passive index composed of 60% equities and 40% bonds to 5,000 actively managed portfolios doing the same. 82.9% of the actively managed portfolios underperformed.

Furthermore, one of the objectives that the remaining 17.1% of actively managed portfolios may not be able to solve is market volatility. For this solution you need to turn to those who can effectively hedge out large swings. This means the consideration of alternative asset managers, including hedge funds.

However, hedge funds themselves are not a panacea. Selection is key, and understanding the idiosyncratic risks associated with different strategies, conducting ongoing investment and operational due diligence, and creating a sufficiently diversified portfolio to hedge against the aforementioned volatility all require deep capital pools, significant infrastructure and very specialised skills.

For these reasons, funds of hedge funds rather than single manager hedge funds may be more appropriate for most investors. Additionally, a recent research paper by JP Morgan has looked at funds of hedge funds as a bond replacement, and has found that they may be well suited as such in the current market environment, generating returns that are comparable to BBB bonds with lower levels of volatility. As the rule applies in conventional markets, identification of an outstanding hedge fund of funds portfolio manager can yield extraordinary results.

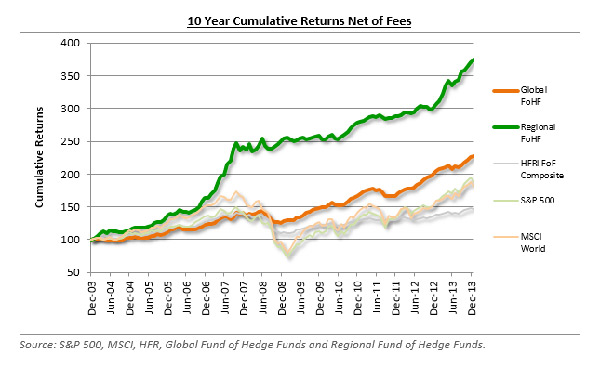

Above you have the net returns for two fund of funds managers, one regional and one global, superimposed on top of the returns for the underlying markets. The returns speak for themselves. In the end, what one feels these types of managers should deliver year in and year out are "sleep at night” portfolios.

The key to the above graph is the word “net". There is much complaining in the press about a second layer of fees paid to a fund of funds manager, which I feel holds little merit. A fund of funds manager is nothing but a portfolio manager who prefers to sit in his office instead of yours and reap the benefits from his performance.

Furthermore, they hold a few other benefits not visible on the surface – access to closed managers, the ability to negotiate better fee and liquidity terms, and importantly the fact that you as an investor can terminate them much quicker than you could restructure an internal team (typically on monthly or quarterly notice).

PATRICK GHALI of SUSSEX PARTNERS says: Time and time again, one has asked charity trustees and charity chief executives/finance directors to honestly compare the net performance, which means after all relevant internal and external direct and indirect costs, of their existing portfolios against an outstanding (i.e. top performing) fund of funds manager in the same sector. The outstanding fund of funds manager comes out on top.

Many charity investors are most concerned with having confidence in their cash flows. The aim therefore is to compound positive returns on a superior risk adjusted basis with a high degree of certainty.

With the "easy money” having already been made, and given the current level of uncertainty, the difficulty of trying to time markets, the devastating effect of substantial draw downs, and on the other hand the potential risk of missing out on continued upside, considering a more flexible approach may be more prudent, than sticking to a traditional portfolio which may be ill suited to sudden changes.