Building charity endowment funds

Persuading someone to part with a substantial sum and assist you in carrying out your good works is not always easy. It can be even harder when you are asking for money to fund a one-off project and plan to spend all the money shortly after you receive it. A better plan, and one which many charities follow, is to ensure that the donor can make a lasting impact on the ability of the charity to achieve its mission.

Building an endowment fund can provide dual benefits; on the one hand encouraging the donor by giving them a sense that their generosity will be part of a timeless force for good and on the other giving charity trustees confidence that they have a long-standing source of funding.

With an endowment they know that they can not only have a decent amount of spending on today’s purposes, but can also have confidence that there will be more available tomorrow to carry on with their tasks.

Many charities do already have endowment funds and some older charities have built up substantial wealth. In general, these funds will tend to achieve the greatest return over time by investing in “real” assets such as quoted shares and property which are closely linked to economic, industrial and population growth. These factors help to drive up asset values over time.

Bond investments

An alternative is to invest in fixed income investments, also known as bonds. As the name suggests, fixed income investments provide a stated level of income each year and a degree of security ranging from very safe in the case of UK and US government bonds, to highly speculative in the case of the riskier junk bonds. As bonds only return the same amount of capital as you invested when they mature at the end of their stated life they can only be used as a source of income.

Whilst shares and property clearly have their part to play in doing the heavy lifting to meet an endowment’s long term capital needs, trustees may decide to hold bonds either to provide a known annual income or to reduce the volatility (or risk) of their portfolio.

Deciding how much risk to take in a charity’s investment portfolio is an important question and will be driven by factors such as the strength of the charity’s cash reserves, its annual spending commitments and the appetite of the trustees or the charity’s supporters to see its endowment fund fluctuate in value over the course of time.

It is important for trustees to differentiate between absolute loss where an investment has failed and a ‘mark-to-market’ loss which reflects a paper loss at the time the investment is valued but may be reversed if the price recovers.

Poor quality

Trustees will naturally wish to avoid owning assets which are likely to fail and lead to permanent loss of capital. They will expect their expert colleagues or their appointed investment adviser to ensure that poor quality assets are not bought in the first place and, if an asset already held declines in quality that it is rapidly disposed of.

Whilst the volatility of funds invested only in real assets might have given trustees the occasional uncomfortable year when the endowment value reflected market falls, a diligent investment approach should produce positive returns over time.

According to the annual Barclays survey, UK shares have produced returns of around 5.5% per annum above inflation over the past 100 years while UK government bonds have delivered around 1.5% above inflation. Blending a share and property portfolio with bonds has the benign impact of reducing a fund’s volatility – the amount by which it rises or falls as the markets move. This can be reassuring for trustees and members, especially when stock markets are very weak.

Lower returns

However, based on the Barclays returns, simple arithmetic indicates that the more safe bonds you put into a portfolio and the less you are exposed to the volatility of the stock market, the lower the return you will make over time.

This is why some of the largest and oldest charities own no bonds at all in their endowments. They take a long term investment view in line with their charity’s long time horizon by buying good quality shares and property which are not going to go bust and do not worry about the occasional bad period in markets.

This investment strategy can be coupled with a “sustainable income” approach where trustees decide how much they can spend each year from the endowment, recognising that this may include a bit of capital gain as well as the natural income on the investments.

Natural income comes from the dividends paid by shares, rents from property and coupons from bonds; it is drawn down and spent each year without any impact on the endowment’s capital. By contrast a sustainable income approach allows a charity to have a defined income each year which it takes from the overall value of the endowment without just relying solely on natural income.

Income level

The level of income which can be taken in this way will depend on the total return target of the endowment, which in turn will be determined by the amount of risk (or volatility) the trustees are prepared to accept.

The total return target is normally defined as “inflation plus x” where trustees with a low risk appetite might target inflation plus 1% over time, with their more adventurous peers invested only in shares and property aiming for inflation plus 5%.

The latter can have some confidence in spending 3% or 4% of their endowment each year, regardless of market conditions, in the expectation that over time the portfolio will still grow by 1% or more above inflation. The alternative would be to aim for a natural income of 3% or 4% to avoiding having to take from capital.

This approach would currently be problematic as only the more risky type of fixed income assets or lower quality real assets will generate income at that level. Neither are likely to give an endowment attractive long term capital appreciation so trustees might also have to accept a return below inflation.

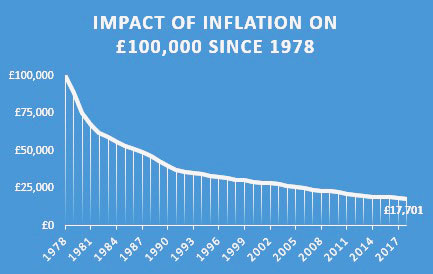

Offsetting inflation

Offsetting inflation to maintain the real value of an endowment should be the trustees’ first priority. Their fixed costs and the value of their grants will all be affected by inflation. Ideally, an endowment needs to produce a decent return over and above UK inflation to pay the charity’s staff and enable the charity to have confidence that it will be able to fund its charitable works.

An endowment can counter inflation in several ways. One, used by pension schemes with long term liabilities, is to invest in inflation-linked bonds. These will certainly do the job, but they also take you back to the low return world which will not give the charity the endowment growth it needs.

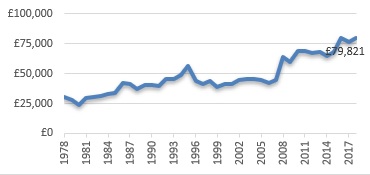

A better way is rely on real assets growing faster than inflation (as they have over the past 100 years) and by diversifying your investments globally to ensure that any weakness in sterling, which is often a consequence of UK inflation, is offset by currency appreciation of the foreign assets owned. The example below shows how the sterling value of a Swiss franc investment of £100,000 would have changed over the past 40 years.

Sterling value of 100k swiss francs since 1978

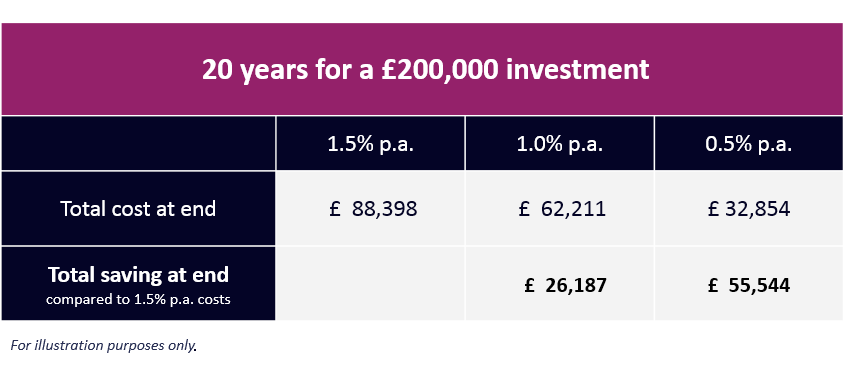

It’s also important to note the impact of investment costs which, like inflation have negative impact on the long term value of an endowment. Trustees should look at investment costs carefully, especially the cost of the underlying instruments which their managers use in portfolios.

Passive investments

The desire to reduce costs explains some of the success of passive investments over the past twenty years as these can shave up to 1% off total costs and tracker investments are being used increasingly by larger charities. The table below shows the positive impact of reducing costs by 0.5% and 1% per year over a 20 year period for an endowment which is enjoying investment growth of 5% per year (gross of costs).

Under charity law, trustees should also ensure that have requisite professional competence when managing their charity’s wealth; this may be via an external adviser unless they consider that they have appropriate expertise themselves. Just putting the money into a bank account with tiny rates of interest is not usually a good answer for endowment money. It needs to be put to work.

Adopting a low risk approach by buying government bonds might seem to a suitably cautious investment of hard-won donations, but is unlikely to enable the charity to maximise its charitable works.

Volatility unimportant

Different approaches will work best for different trustee bodies but the important things to remember are that volatility in the fund value does not matter unless you are planning to sell assets in the near term and that failing to match inflation will eventually run down the value of the endowment. With the right investment policy the charity will be able to spend more in the future as the investments go up in value and generate more investment income.